It’s about time that I shared one of my big plusses from my 2017 Summer Intensive experience: “hunting” Quechua, thanks to Rachel Sprouse. It makes learning to hunt a lot more real for me since Quechua is a language I’ve been trying to learn (on and off) since 2013. My first link to Indigenous languages in the Americas was with Quechua when I found out about worldwide language endangerment. I’m also happy to be able to practice hunting in Chinese (with Chinese speakers Erin McGarvey and Myles Creed), but Quechua is especially relevant since it’s an Indigenous language under pressure and, in the future, I hope to work with Quechua speakers and learners on language revitalization.

Hunting Quechua is a great head start to working with Quechua-speakers in two ways. Firstly, there is a lot more credibility to promoting an Indigenous language when one has taken the trouble to learn it oneself. During our conversation about the ins and outs of learning an Indigenous language as a non-Indigenous person, Evan Gardner mentioned that there is a value to just showing “that it can be done”.

Secondly, there are ways that WAYK techniques need to be adapted to each particular language-culture, and we have already made a good head start on that. It’s only by starting to hunt and teach the language that you realise the specific challenges that come up for each language. These challenges include deciding which hand signs to lay over the spoken language, and how to scaffold different bits of language. To show what I mean, I will quickly describe what happened when Rachel practised giving a Quechua “ride” (WAYK speak for lesson…but more fun) to me and Evan.

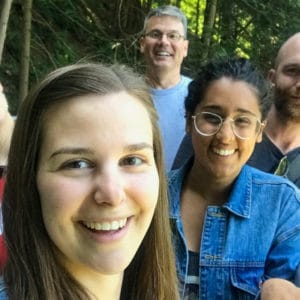

Rachel Sprouse and Robbie Penman during a Quechua hunt on St. Paul Island, Alaska.

During a Quechua hunt, Robbie takes a loaf of freshly baked bread out of the oven as Rachel looks on.

Rachel Sprouse and Robbie Penman bake bread during a Quechua hunt on St. Paul Island, Alaska.

Rachel created a great ride using techniques Make Me Say Yes and Make Me Say No, asking the questions “what is this?”, “is this a condor?”, “is this a fish?”. In Quechua, you have to use -chu in order to form a question or to form a negative sentence. So we had to decide how to sign -chu; and, perhaps more interestingly, whether it should be one sign or two. On the one hand I thought that it should be one sign, thinking that it’s probably a European language bias to think of these two meanings as separate meanings, and that part of learning Quechua is learning to think of questions and negations as similar in some way. On the other hand maybe there is some evidence that they are separate words (I don’t know enough Quechua to judge); and, even if -chu has just one meaning for native Quechua-speakers, it may be more helpful to Spanish-speakers or English-speakers to separate the question meaning and the negation meaning, at least when they are just starting out learning the language. I don’t have an answer to this issue, but it illustrates nicely the kind of question comes up when laying sign language over spoken language. Having thought about these issues already will make it a lot easier to teach WAYK to anyone who wants to use it specifically for Quechua.

Getting to learn more Quechua is something I wasn’t expecting from the summer. Although I was (and am) curious to know more about North American languages/cultures, I was pretty much expecting South America to be out of the picture for the summer. But this wasn’t the case! It’s also exciting to think that this could be the beginning of using WAYK techniques to help the revitalization of South American languages.

Post authored by Robbie.