The challenge of designing the ultimate Turkish hunting kit has captured the obsessive part of my brain for the last week. What is a “hunting kit,” you ask? It’s a collection of objects carefully chosen to introduce a language to a learner.

One example is the Unangam Tunuu hunting kit. In one of our first lessons, speakers named all the objects slowly with repetition. We understood that there was something important happening with the word endings “-ax̂”, “-ix̂”, and “-ux̂,” because the speakers grouped the objects into those three categories.

How is a hunting kit different from, say, a box of props? A hunting kit is more specific. It’s designed to anticipate and clarify particular challenges in the language, including pronunciation and grammar challenges, rather than just vocabulary. Going back to the Unangam Tunuu example, that hunting kit anticipates issues with the three endings for nouns, and helps learners keep them clear from the start. We may end up using different sets of props for specific activities – a kitchen props box to talk about cooking, or a costume props box to talk about getting dressed – but we only have one hunting kit.

From what I have seen, the hunting kit is connected to many of the first lessons – or “rides” as we call them in WAYK – in a language. Learners use the same objects again and again. The objects become familiar and even “talismanic” to use Evan’s word. To give an example, if you pull out a chaagix̂ prop, my brain prepares to use Unangam Tunuu, whether it’s talking about having a chaagix̂, wanting a chaagix̂, or counting chaagix̂ (chaagin). We use the hunting kit in our foundational lessons, as well as in new scenarios going forward.

Different languages will demand different hunting kits. A Chinese hunting kit, as Evan showed me, should probably include all four tones of Chinese, since that feature is important to the language. A chinuk wawa hunting kit should probably include items that relate to each other because that language, in particular, requires you to make concepts by using words like building blocks.

What about Turkish? What would the ultimate Turkish hunting kit look like? For whatever reasons, teaching Turkish is a dreamy wonderful thing that I always want to do or think about, so this became my question and quest.

I turned to the “Perfect Props for WAYK” poster for inspiration in starting the collection.

A perfect prop should be:

- Extremely obvious

- East to say in the language

- Easy to find – many that are identical

- Easy to hold

- Easy to pass back & forth

- Things you talk about frequently

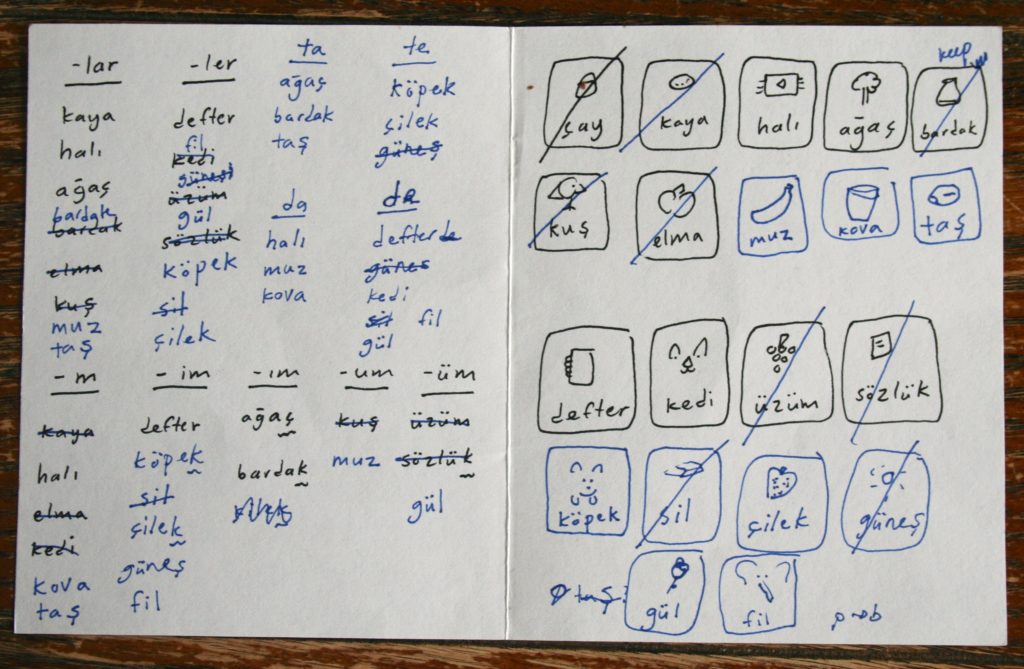

It turns out that this is a tall order. I started with a bunch of items, then quickly started crossing them off and adding others. The big leap was when I started considering the first foundational rides that a learner would go on in Turkish. Mapping out the first ten rides helped me choose.

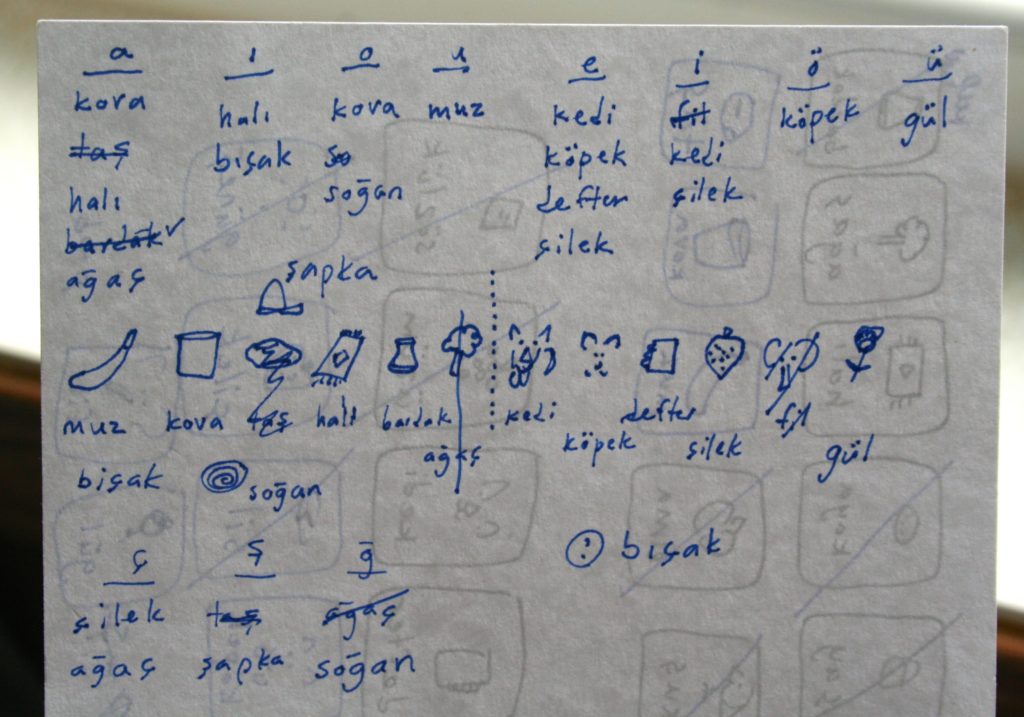

As of now, I am including eight objects, each a placeholder for the eight vowel sounds of Turkish. Because of Turkish’s “vowel harmony”, differentiating these sounds and working with them early seems important to unlocking the language.

Talia was kind enough to be the first guinea pig for an initial Turkish ride with the kit, which took about seven minutes. Evan and Erin went next, taking eight minutes. Their feedback was extremely helpful, and they helped me decide that the “a” sound object should be an araba instead of a şapka. The hunting kit will likely change again and again. I am excited to test it more.

Post authored by Mary.