In the last couple of weeks I’ve been learning how to “hunt” language. When I first heard what people meant by “hunt” in WAYK-speak, I wondered: is this what I learnt to call “elicitation” in my classes on linguistic field methods at SOAS (my alma mater)? I’ve decided that the answer is: not exactly, but the two practices have a lot to learn from each other, which is why I decided to write this blog post. I also hope that looking at hunting in comparison to elicitation will help to clarify what “hunting” means for any readers of this blog post who are more familiar with the world of language documentation and description.

Before going into the differences between hunting and elicitation, I’ll quickly outline how I understand the two terms. Hunting, in WAYK terminology, is when you talk to someone with the aim of getting better at a language (the language in which you’re both speaking). Below I also use the term “hunter” to mean someone whose main aim is to become fluent, as opposed to a “documentary linguist” whose main aim is to document and describe a language. Elicitation is one method that a documentary linguist uses to get linguistic information in order to document and describe a language. Claire Bowern (2008:8) 1 describes it as “asking questions about the language” (emphasis in original), in comparison with “data collection by other methods, including free conversation, narrative recording and interviewing”.

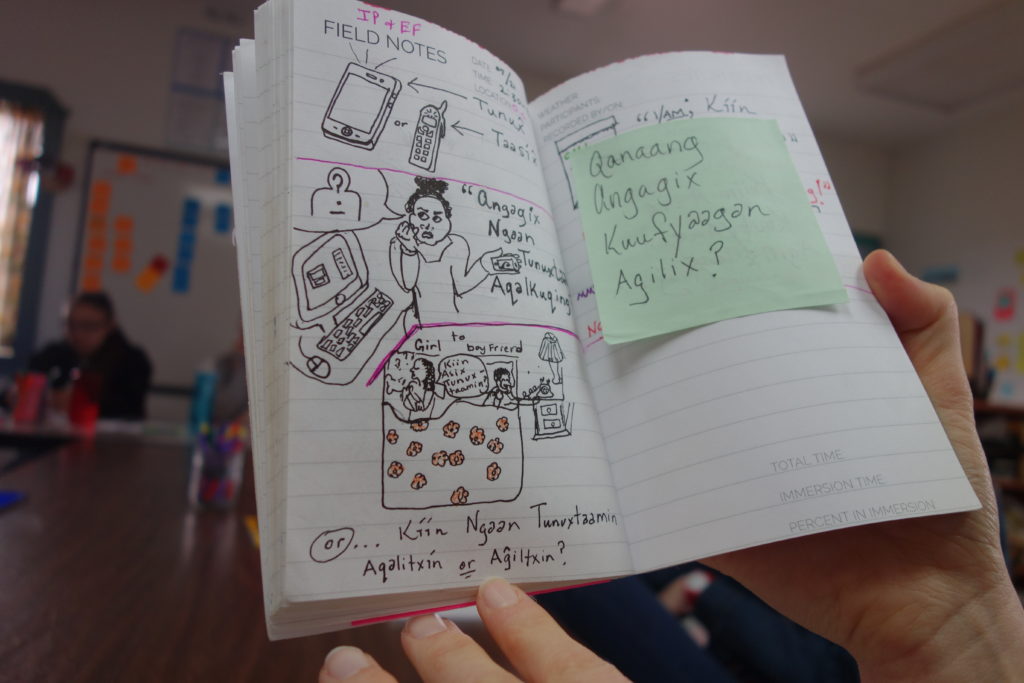

Me and Tanĝaĝaadax looking at example ‘hunting books’ for taking language notes after hunting sessions and planning for upcoming sessions.

Hunting and elicitation are similar in that they both involve someone with less language knowledge trying to get some from someone who has more. This process creates a need for some kind of workflow: making notes on pieces of language learned, noting metadata (e.g. date of the session, who was speaking), and planning for the next session. The hunting workflow I’ve been learning with WAYK is very similar to that which I learnt for elicitation sessions, although it’s trimmed down by (a) not making recordings and (b) not providing translations in session notes. The fundamental difference between hunters and documentary linguists is what they then go on to do with that new knowledge (see below).

Before going onto the differences in more detail, a caveat: In talking about both hunting and elicitation I’m thinking of the classic challenge they both face: how to “create meaning”, i.e., have a speaker produce language without having just them translate from English, Spanish, French, etc. (As we all know, translating in that context kills fairies … and worse!). There are other aspects to good hunting and good elicitation practices that are less “linguistrict” (strictly linguistic) such as relations with the speaker, or the social context in which both happen (research vs. community language revitalization). These are no less important, but I don’t deal with them here for reasons of space.

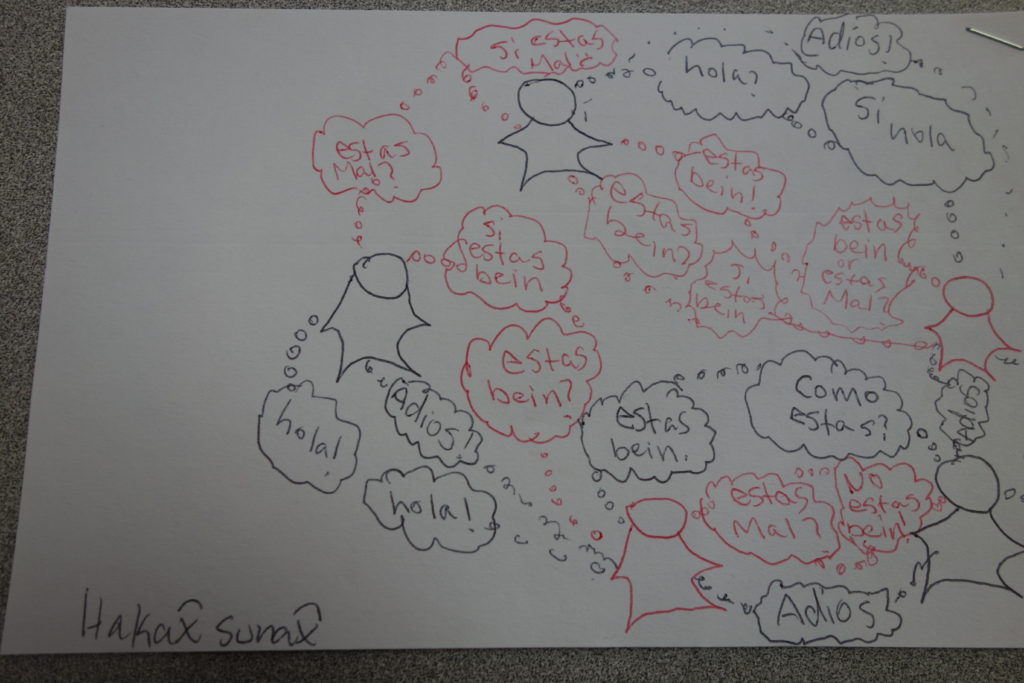

The two differences that have struck me are to do (1) translation (vs. TQs Set Up/Prove It), and (2) planning for the next session. On translation, Claire Bowern (2008:78) writes that “the most common method of elicitation is to have your consultant(s) translate sentences into the target language”. I don’t know if this state of affairs in documentary linguistics is really because linguists don’t recognize the dangers of translation (although documentary linguistics could probably benefit from some input from translation theory), but translation is often simply assumed as the main method of elicitation (e.g. Chelliah & de Reuse 2011:212)2. Perhaps the explanation is simply that linguists have not yet come up with many alternative methods (or methodologies…?) for conveying meaning to a person so that the person can then express that meaning in the target language. (An example of an exception is the visual stimuli developed by the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.) In which case there is important skill that documentary linguists could learn from WAYK: how to “set up” (including triangulation) and “prove it”. For example, rather than translating “the bread has risen”, you can show a speaker bread dough before it’s risen, and an hour later ask them what has happened to it. Then triangulate it with at least two other instances of things changing; then test it by using the same grammatical structure for something else, e.g., mold growing. The process of triangulation might well need to occur more than once, in order to know what was relevant: was it that the bread started rising this morning instead of today? Was it that the tide was rising rather than the bread? And so on.

In fairness to documentary linguists, they need translation in a way that it isn’t for language learning. This is because documentary linguists are producing a stable record of meaning, rather than just keeping it in their heads, and so far there is no good way of writing down the meaning of a string of unknown language other than translating it into a known language. There are many, many meanings in Unangam Tunuu or Quechua that can be much better conveyed in English or Spanish than in a string of cartoons or cut-and-break videos.

“Set up” and “prove it” also allow the whole session to remain in immersion (in the target language), whereas translation by definition breaks immersion. Many documentary linguists recognize the advantages of becoming fluent and carrying out elicitation in the target language, but do not discuss specifically how to do such elicitation. More generally, they do not discuss how they learn a language when no learning resources are available other than the speakers themselves, and WAYK offers one way of doing precisely that. If one reaches a high level of proficiency in the language, the exact “how to” of elicitation becomes less of an issue, but how does one reach that high level of proficiency? By focusing only on becoming fluent before documenting anything? This seems like a wasted opportunity, given the basic similarity between hunting and elicitation. Instead, those who don’t want to see their language disappear could fuse hunting with elicitation, aiming both to become fluent and to create a lasting documentation of the language for others.

The second difference between hunting and elicitation comes from the question: how do we decide what bit of language to hunt/elicit next? For a hunter, the answer is: whatever pieces of language have come up before that you didn’t understand. More specifically, it may be a good idea to focus on things you didn’t quite understand, rather than pieces that are totally new to you (see TQ “Familiar ground”). This is also a common recommendation to documentary linguists. However another kind of consideration usually comes into play, to varying degrees, for a linguist. Namely: what happens in other human languages? An illustration of this is the “analytical questionnaire” (see e.g. Chelliah & de Reuse 2011:362–363) following a schedule (Samarin 1967b: 108-112).3 For example, knowing that some languages distinguish between “we” meaning the speaker and the person they’re speaking to, versus “we” meaning the speaker and someone who isn’t present, you might make a set-up to check whether speakers of Unangam Tunuu do the same thing.

In light of the differences I have written about above, one way for hunters to learn from linguists might be to take advantage of the rough road-maps of possible language features that linguists have been working on for decades. However, this suggestion is less relevant to people who are learning relatively well-described languages; they needn’t worry about all possible features of human language, only the features that show up in their language. Some work would also be needed to make these road-maps accessible to learners without a background in linguistics. Aside from this, there are things to learn from best practices in documentary linguistics regarding how to keep metadata, take language notes, and use recording equipment (if hunters record their sessions).

For documentary linguists, I hope that this comparison has highlighted the value of learning hunting techniques, in order to get at the target language without the influence of a dominant language. I also hope it furthers the view that learning to “set up” and “prove it” is a skill. It’s a skill that can be taught and learnt, and a skill which it takes a long time and much practice to become expert at. And it’s a skill that should be one of the main things a linguistics student learns if they take a “field methods” type course, because it’s fundamental to the whole premise of documenting and describing languages on their own terms.

Post authored by Robbie.

- Bowern, Claire. 2008. Linguistic fieldwork: a practical guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chelliah, Shobhana L. & Willem J. de Reuse. 2011. Handbook of descriptive linguistics fieldwork. Berlin: Springer.

- Samarin, William J. 1967. Field linguistics. A guide to linguistic fieldwork. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.