One of the things that has struck me so far about this summer has been the “organization” of the team. That word alone doesn’t quite capture what I mean; maybe a better one would be “organizational culture”, a term I’m not that familiar with but seems to do the job. It’s something that has interested me more and more in the last year or so. (Someone joked that maybe I should forget about indigenous languages and go into management or business back in London.) I think a defining moment was listening to Frédéric Laloux talking about “reinventing organizations” (his full talk is on Youtube). Spending time in several intentional communities (try www.ic.org) made those issues very real.

One of the things that has struck me so far about this summer has been the “organization” of the team. That word alone doesn’t quite capture what I mean; maybe a better one would be “organizational culture”, a term I’m not that familiar with but seems to do the job. It’s something that has interested me more and more in the last year or so. (Someone joked that maybe I should forget about indigenous languages and go into management or business back in London.) I think a defining moment was listening to Frédéric Laloux talking about “reinventing organizations” (his full talk is on Youtube). Spending time in several intentional communities (try www.ic.org) made those issues very real.

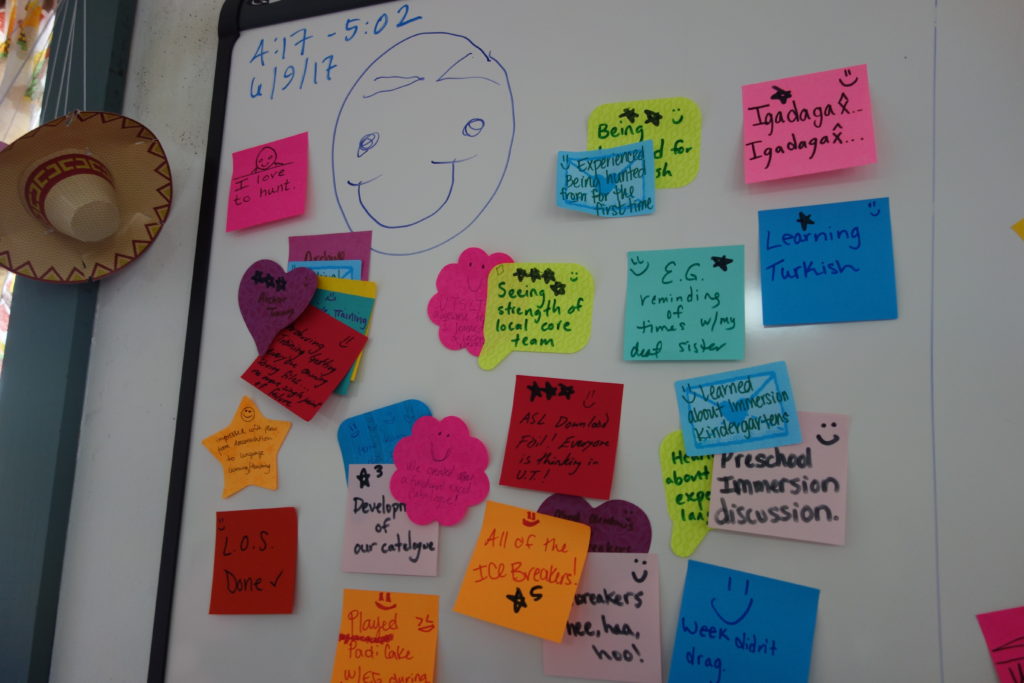

Now, a large part of organizational culture is to do with the way people talk to each other, and I’ve begun to see an exciting relevance of what I’ve studied academically (linguistics and the social sciences) to very specific problems coming up in the way people organize themselves in group activities. So it’s satisfying to be learning more tools (with great names like swimlanes, short-term parking, rock piles, scrum, etc.) to solve those problems.

And we just happen to be applying those tools to a language revitalization initiative, meaning that what we’re learning about organization is linked to language (and language diversity) in two ways. The first way is that we are using them to help language revitalization as a whole, because language revitalization is a social movement (like the civil rights movement, permaculture, religious proselytizing, etc.) that can use organizational techniques and methodology to increase its success.

The second way is that these techniques are themselves “made of language”: for example, saying “how fascinating!” when we learn something fascinating and when we make a mistake in order to blur the boundary between the two (or, to put it better: to help us realise that maybe there is no boundary in the first place). Over time these techniques can become crystallized into the language in words such as “facilitation”, or phrases such as “I invite you to …” (as a way for a facilitator to have people in a group do something).

So far this might seem irrelevant to languages under pressure, like Unangam Tunuu under pressure from English. But everything from learning the Unangam Tunuu word for sea (at one end) to how we give each other feedback (at the other) is part of the same arc of creating new language/culture…something which all humans are doing all the time anyway, just a little more obviously and consciously in the case of language revitalization.

One benefit to becoming more aware of this arc is to clarify what “revitalizing” a language means. In my opinion, it doesn’t mean “simply” replacing English or Spanish words with Unangam Tunuu or Quechua words; it means thinking about all aspects of the way people communicate with each other. And in doing so there is something to learn from the ways that indigenous language communities in Alaska or the Amazon hold meetings, make decisions, schedule activities, allow space for feedback, and so on; just as there is something to learn from the ways Amazon or Google do the same things.

Post authored by Robbie.