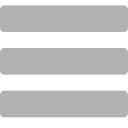

George and Aquilina modeling a “cocoa talk” in front of elders in St. Paul

I have been thinking about the relationship between a language learner and an “informant”, who may be a native speaker, a fluent speaker, or just someone more proficient than the learner.

Here on St. Paul Island, local language team members have been improving their fluency by “language hunting” with some of the elders who either live here or come to visit. During language hunts, the team members use Technique: Same Conversation and Technique: Hunt On Familiar Ground to have familiar conversations that they can understand. They use Technique: Set-up and Technique: Bite-Sized Pieces to create situations that bring up new language in manageable pieces. Throughout the interaction, they will likely bring in additional techniques with the elders to try to slow them down or have them repeat key pieces, among other things.

All of these techniques are useful, and the elders will respond to them differently – some ignoring them, some understanding them, and some even beginning to adopt them – but I wonder about the relationship dynamics. Does the nature of the relationship impact language learning even more than these techniques? From what I’ve observed, it’s rude to interrupt elders or to explicitly redirect them. The important thing is to listen. This may be especially true for a younger person, and many of the local team are teenagers. These dynamics may present certain challenges for language learning.

The Summer Intensive group quietly observing a conversation between elders.

I compare this situation in St. Paul with my experience in language exchanges, in which two people meet regularly and spend half the time in the language that Partner A wants to learn, and half the time in a language that Partner B wants to learn. Both people spend time being “teachers” and “learners”. In the course of a session, both have the chance to feel confident, knowledgeable, helpful, and generous, as well as confused, hesitant, challenged, curious, and appreciative. This reciprocity acts as an equalizing force, even if there are differences in age, background, or social status. The result, ideally, is that people feel increasingly confident managing each other during sessions, to make the most of their time together.

In the case of indigenous and endangered languages, I understand that it is mainly elders who are the language “informants,” if a community has speakers left. This prompts in my mind the question of how to make the most of interactions, while still following social codes and protocols. How do you respect your elders, without falling into an ocean of incomprehensible language, and just nodding along out of politeness? I wonder if one answer might be to audio record or video record conversations, and later listen and break it down with other learners, still in the language? What other ideas are out there, or in use? I’m curious to think more about techniques that deeply take into consideration the importance of the relationship between learners and speakers.

Post authored by Mary.