One way to describe a summer with WAYK is that it provides the on-the-ground work experience that should be part of any training in language revitalization and documentation. In this blog I’ll describe it in these terms, mainly by contrasting it with the only other “official” training I’ve had, a masters degree at SOAS in London.

My degree didn’t include an experience like this, although both my degree and my summer with WAYK have given me valuable tools to apply to language revitalization and documentation. I feel lucky to have had both these experiences, and at the same time, it is a shame that both aren’t available to everyone. Unfortunately, it seems that a practical experience like a summer with WAYK is not really included in any of the few course-based degree programs in language revitalization/documentation, on offer at the University of Victoria, the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, and SOAS. (Judging by the information available on the University of Victoria’s website, their three programs are the closest that the academic world comes.) So one reason I have for writing about this topic is to encourage the academic world to recognize the importance of this kind of experience.

To provide a contrast to what I’ve been learning with WAYK I’ll quickly summarise the kinds of knowledge/perspectives/benefits I gained from my degree program:

- a big picture on language endangerment, revitalization, and documentation worldwide (particularly in terms of the well-known language revitalization “success stories” such as Māori, Basque, Welsh, or Hawaiian)

- linguistic theory and descriptive linguistics, especially questions about what is universal and what is specific to particular languages/cultures

- technical aspects of language documentation, including recording equipment, file management, and software

- knowledge of specific revitalization and documentation initiatives around the world, and in the case of Basque, Irish, Quechua, and Manchu the chance to meet speakers and learners of these languages

In contrast, I would summarize my summer with WAYK as being more holistic, and I’ll try to explain what I mean by that. The summer has shown me more clearly than before the myriad ways in which strictly linguistic phenomena (can we call them “linguistrict”!?) are linked to questions of ethics, social relations, group organisation, politics, economics, and so on. I have learned how to better manage these intricacies, especially my own position as an outsider; and also become better at recognizing that sometimes there is no perfect solution, and that the work is a constant process of negotiation between different perspectives and values. My time with WAYK has also shown me that in a moment when I suddenly need to apply knowledge of linguistics, the academic divisions between theoretical linguistics, sociolinguistics, second language acquisition, and so on may become blurred, inadequate, or irrelevant in the face of the issue at hand. Of course this also applies to all the skills and knowledge that someone brings with them to a summer with WAYK, whether from linguistics, other branches of the human sciences, teaching, community organizing, or anything else. The last thing I have in mind when I use the word holistic is illustrated nicely by a discussion we had about our goals for the summer. I said that one of mine was to work out how to balance language revitalization/documentation, academia, finances, and life in general. Now, after the summer, I feel more confident in doing this balancing. This has a lot to do with seeing others achieve this balancing act, especially when they manage to do so with good humour and grace.

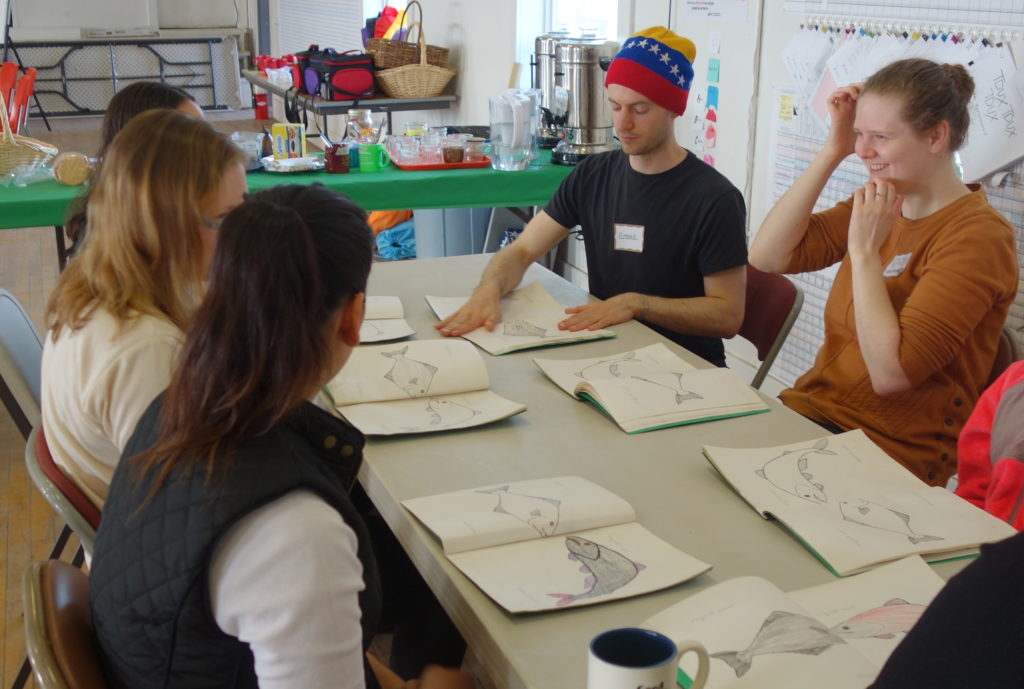

Going through a ride at the Unangam Tunuu Download Camp.

Me and George at the feedback session for the summer.

Having said that my summer with WAYK has provided this more holistic experience, “how has it done this?” is probably the next relevant question, especially for anyone else who wants to replicate this kind of training. One of the answers is living in what I’ll call “language revitalization immersion”, i.e. working on language revitalization from nine to five, Monday to Friday, living in a house with other people doing the same, and getting more skilled at language learning/teaching in our spare time. Another answer is living in the place where both the elder speakers and young learners live, which is more or less a must if you are going to be working every day on language revitalization. And another is learning an indigenous language of the Americas, which often means learning by hunting since it is hard or impossible to learn by being in immersion in many (perhaps most) indigenous-language communities across the two continents.

Many of the things I’ve learnt this summer are things that inevitably cannot be taught in university classes; although I had experiences on my degree program that were closer to the WAYK experience, particularly organizing Quechua classes at SOAS. I’ve also had experiences this summer that were more on the technical side of language revitalization and documentation, such as archiving recordings. Both university-type knowledge and WAYK-type knowledge are important to working in language revitalization/documentation, and it’s worth emphasizing that one being more holistic and the other more technical doesn’t mean that one is more valuable than the other. To build a house well you need knowledge of structural engineering, just as you need the experience of living in a house.

Post authored by Robbie.