Here’s Robbie Penman’s update from the fall of 2017, a few months after his summer with WAYK on St. Paul Island, Alaska. Thanks for the update, Robbie!

*Jerky is one of the few Quechua words in English

At the end of August 2017, I came back to the Ununited Kingdom (note to Susanna: that’s deliberate!) after my summer with WAYK on St. Paul Island, Alaska. This blog is about what I’ve been doing since then. I’ve arranged the blog time-wise, from September to December, but also anti-clockwise – around Europe and European languages, from Scotland to the Basque Country to Portugal to (ancient) Greece to Poland.

As September dawned, I was surrounded by a sea of English (again!) – I knew I had to act quickly to keep my language faculty rust-free and apply it to a language in need. So I joined a distance-learning course for Scottish Gaelic run by Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, which involves a weekly lesson over the phone and self-study using audio files in between. That’s a way of learning a language that’s about as different from WAYK as you can get, but partly for that reason, I thought it would be good to experience it. It’s been interesting to see (or rather, hear) how the tutor runs a beginners level class in immersion over the phone! And to find out how a distance-learning course is run—I think it could be relevant to learners of South or North American languages, who often lack opportunities to use their language simply because they are somewhere with no other speakers.

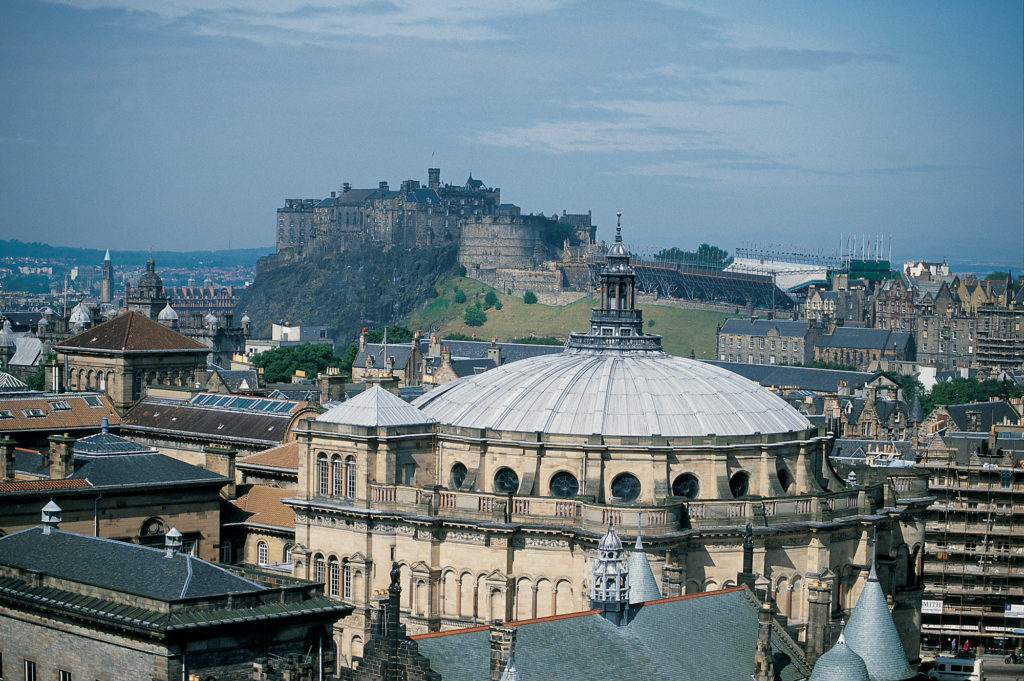

I’ve also used Gaelic with real people by going to conversation circles (cearcall còmraidh) in Edinburgh, which are on almost every day of the week. I was also lucky to be in Edinburgh during “Gaelic week”, and in that week I began to understand a bit better a quote I heard in a film (unfortunately I can’t remember which one) at a Native Spirit Film Festival: “learning my language is saving my life”. I didn’t know anyone in Edinburgh at the start of September, and without Gaelic, I might have spent my time there alone. Is it just the fact that language revitalization brings people together that makes it good for them? Is it just as effective, in that sense, for people to join a Tai-Chi class or book club? Or Japanese classes, for that matter? (Maybe the latter is a more appropriate comparison.) I feel that it’s something more than just bringing people together, although I can’t yet explain why. Robert MacFarlane’s Landmarks, a well-chosen birthday gift to me from my Mum that I’ve been reading at the same time as learning Gaelic, gives some pointers in that direction.

In October I went to a conference in Portugal entitled Communities in Control: Learning tools and strategies for multilingual endangered language communities (what does the choice of title say about who has been in control up until now…?). My presentation was about WAYK and the UTSLT team on St. Paul —specifically, how and why they run sessions that are simultaneously language revitalization and documentation (the full paper is here). Of course, despite all the preparation, there were definitely things to be improved on in the way I presented things. For example, I wasn’t clear enough whether my suggestions were aimed at outsider linguists or community members: I think certain techniques (e.g. the Max Planck stimuli) can be great if you’re doing research, but not if you want to learn the language. In any case, I learnt a lot from the experience of presenting about WAYK and about a community that’s using it.

On my way to and from Portugal, I hopped off the train in the Basque Country to stay with my good friend Beñat, language activist and first-class guide specializing in personalized language revitalization tours. We spent a day with participants on the degree in “strategies for development and revitalisation of language and native identities” organised by the NGO Garabide. I was happy to see a couple of familiar faces on the course, one of whom was there because I mentioned the course to her back in 2015! I went to one of the Hitz Adina Mintzo talks that Beñat organises. These are held every month or so on the situation of a particular minority/indigenous language, and the talks are usually held in Basque. I was amazed to learn, for example, that Roberto Awa Nari from the Peruvian Amazon will be talking about his language (Kokama) all in Basque!

I also met up with Basque friends who work supporting language revitalization in Latin America (see, for example, Mugarik Gabe). Speaking to Ane Ortega in Bilbao I was interested to learn that even language activists focussed exclusively on revitalization (rather than documentation or description) have found it helpful to make high-quality video recordings of interactions in the language in order to use as learning and teaching materials (this relieved a few doubts in my mind about focussing on language documentation for my PhD.) And the whole time I was in the Basque Country I got to see how people react to being addressed in Basque (rather than Spanish). For me, this was an exciting social game that played out at every interaction with a stranger. But, as Beñat pointed out, it can be exhausting and risky for actual speakers of the language who have to play the game every time they go into public.

In November I’m going to meet the Language in Conflict team at the University of Huddersfield, who apply insights from linguistics to conflict prevention and resolution. I see this as relevant to language revitalisation (and WAYK) in at least three ways, although I’m still trying to get my head around it. (Something else that I’ve been doing the last few months is writing a book chapter for the Handbook of Language and Conflict that the Huddersfield team is editing.) For one thing, language revitalisation often takes place in contexts of conflict, or at least tension, between ethnolinguistic groups – that’s certainly the case in the Basque Country, Northern Ireland, the Wallmapu (Mapuche territory), many parts of Colombia, and Quebec, to name a few cases. For another thing, the ways in which people deal with differing opinions, interests, perspectives, etc. depend upon their language and culture. So part of what is lost when a language disappears is a unique way of dealing with conflict (or potential conflict). And for yet another thing, language revitalisation itself is an activity in which people have to accommodate their differences. That means that an awareness of conflict prevention and resolution strategies can be very helpful to the enterprise.

In November I’ll also carry on hunting Greek from my mum. I told Susanna Ciotti I’d be hunting Latin from my mum, but when I heard Greek it suddenly seemed so much more exciting! It’s an interesting exercise for me to be hunting language from someone I’m so close to, since I know that’s the situation a lot of WAYK-players and language revitalization activists are in—although in my case, of course, I don’t face the added pressure that my mother is one of the last people who speaks Greek. At the start, it was also interesting to have to “explain WAYK” (a challenge I also faced with speakers of Gaelic and Basque). Everyone I’ve done this with has responded to my explanation by saying “and what should I do?”—a question I wasn’t really prepared for at first, and I’m still not sure how best to respond.

In December I’m going to Poland for several days training in “participatory democracy” aimed at participants from several EU countries and organised by Betzavta. I was encouraged to apply to Betzvata by a summer with WAYK thinking about group facilitation, group decision-making, group living, and group everything. The training isn’t much to do with language revitalization directly, but it is intended to promote understanding and tolerance of cultural diversity (and, correspondingly, linguistic diversity). I think it’s significant that the Kreisau Initiative, where the training is being held, is so close to the old concentration camps of Oświęcim (Auschwitz).

After Christmas, I’m planning to get back to South America to put some WAYK into practice. I’d be the first to acknowledge that, while all of the above has been very interesting for me, none of it is directly useful to speakers or learners of South American languages. But there’ll be another Mapuche-Williche language camp at the end of January in Melipüllü (A.K.A. Puerto Montt), and probably more throughout 2018. I’m also planning to go back to Peru to get a head start on my Ph.D. project, incorporating everything I learnt with WAYK into the process (more details on this to come…).

Aside from language business, I’ve been at home in the Lake District planting trees: on the one hand haunted by thoughts of climate change, the supermarketization of food culture, social division; on the other hand inspired by the creativity and beauty of human responses (under labels including permaculture, forest gardening, agroforestry, etc.) to all of this.

Post authored by Robbie.